Sharing knowledge

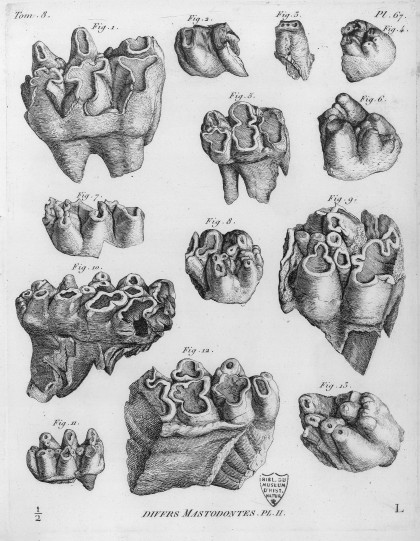

Collections and publications

Plate 67, in Annales du Muséum d'histoire naturelle, tome 8, Georges Cuvier, 1806. © Paris, Muséum d'Histoire naturelle

The emerging Spirit of Europe was fueled by an intellectual effervescence and knowledge-sharing that had little or no regard for national boundaries. Thinkers, objects, books and ideas moved freely between countries inspiring innovative projects, a phenomenon attested to by the Humboldts' ambitious undertakings. And it was by nourishing their international networks and generously sharing the fruit of their work that the Humboldt brothers were able to accomplish their great universal project: contribute to a better understanding of both Nature and Humankind.

A monumental editorial undertaking

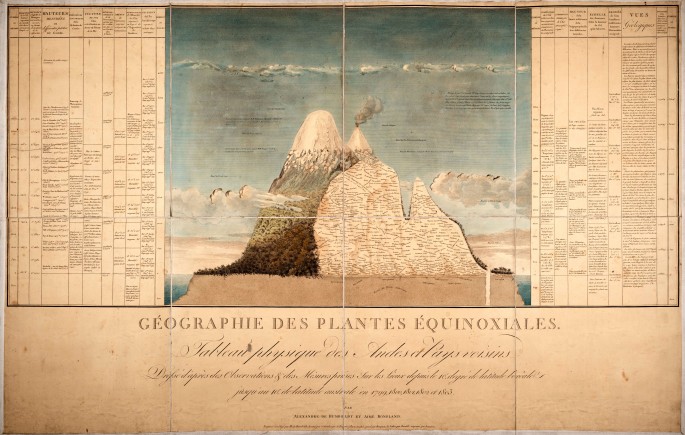

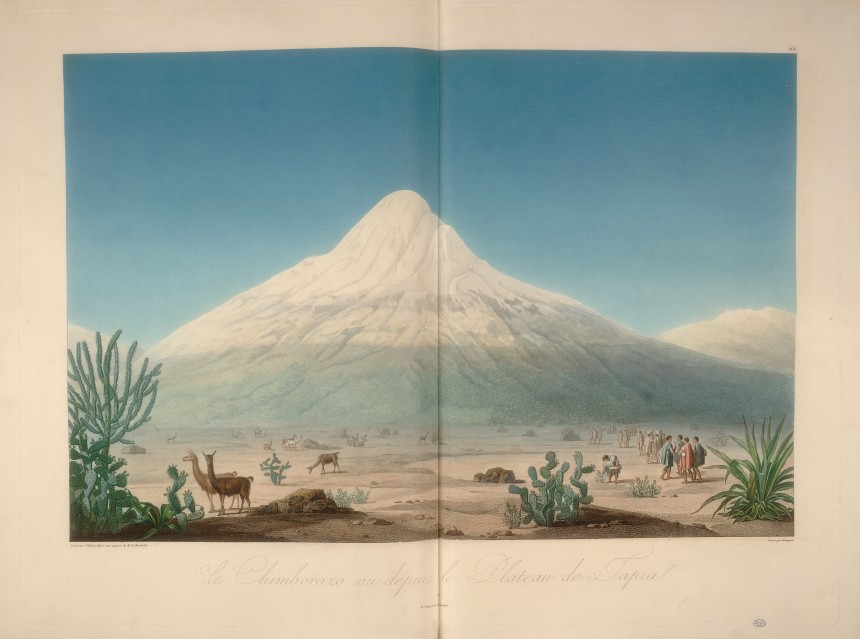

Once back in Europe, Alexander devoted much of his time to publishing the narrative of his American Expedition. It took him close to thirty years to complete the 30-volume Voyage aux Régions Equinoxiales du Nouveau Continent, fait en 1799, 1800, 1801, 1802, 1803 et 1804 (Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America, during the years 1799-1804).

In 1810, Alexander began publishing his Vues des Cordillères et monumens des peuples indigènes de l'Amérique (Views of the Cordilleras and Monuments of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas), a work at the crossroads of science and literature. The engravings, based primarily on Alexander's original sketches, are both precise scientific illustrations and works of art in their own right. They are the fruit of a Europe-wide collaboration between Italian, German and French artists. As for the text, it comprises both Alexander's American field observations and the comments and opinions of the numerous scholars with whom he exchanged following his return, including Ennio Quirino Visconti, the most eminent European archeologist of his time, to whom the work is dedicated.

Alexander von Humboldt (author), Aimé Bonpland (author), Jean-Thomas Thibault (artist), Louis Bouquet (engraver), 1810, Colored engraving, 50,8 x 68,5 cm, Paris, Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Bibliothèque centrale du Muséum, © Paris, Museum national d'Histoire naturelle

Humboldt and Bonpland's 30-volume Voyage aux Régions Equinoxiales du Nouveau Continent, was one of the most ambitious publishing projects of the time, comparable to the 23-volume Description de l'Egypte (Description of Egypt) published between 1809 and 1829 by order of Emperor Napoleon le Grand.

The world portrayed through maps

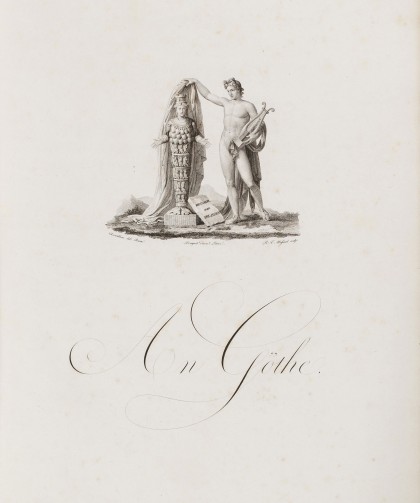

The Humboldt brothers first met Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, one of the most prominent German intellectuals of their time, in Weimar where Wilhelm lived from 1794-1797; and the three developed lasting ties. Goethe and Wilhelm shared a fascination for classical Antiquity and an interest in philology and linguistics. With Alexander, Goethe shared a passion for mineralogy and botany.

The three Berlin scholars' shared interests and mutual esteem resulted in two distinct projects that, while they focused on very different topics, both sought to represent the world using practical tools.

Map of the Equinoctial Regions

In 1807, Alexander dedicated one of his first books, Ideen zu einer Geographie der Pflanzen (Essay on the Geography of Plants), to Goethe. Alexander sent Goethe a preliminary print in German, promising to send him the missing table at a later date

Instead of waiting for the missing document, Goethe decided to construct his own map based on the data contained in the book. His illustration, a colorful composite landscape, compares the mountains of the Old and New World. Goethe's map was so widely reproduced and distributed all over Europe that it is better known than Alexander's original.

Alexander von Humboldt (author), Aimé Bonpland (author), Anne-Charlotte de Schönberg (draughtswoman), Louis Bouquet (engraver), 1805, 53,5 x 83 cm, St. Louis Missouri Botanical Garden, © St. Louis Missouri Botanical Garden, Peter H. Raven Library

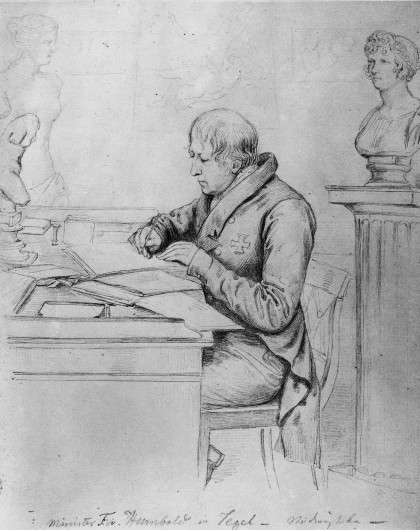

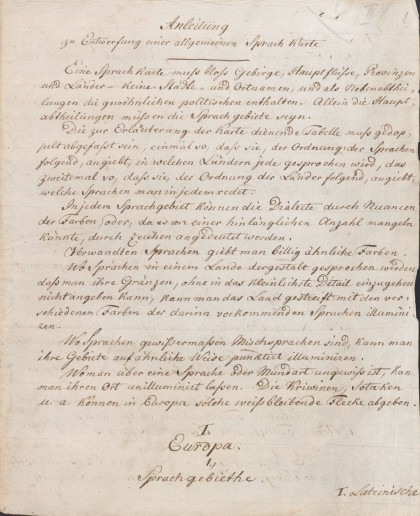

Wilhelm von Humboldt, 1812, Encre sur papier, Weimar, Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Goethe und Schiller-Archiv, inv. GSA 78/300, © Klassik Stiftung Weimar

Les langues de l’Europe

En 1810, Goethe suggère à Wilhelm d’illustrer une carte répertoriant les langues parlées dans le monde. Moins doué que son frère pour la cartographie appliqué, Wilhelm se content de décrire la carte idéale. Il adresse par écrit ses instructions à Goethe, un texte de dix-neuf pages que Goethe commence à transposer en image. Aucune trace du dessin n’a été malheureusement conservée.

Cependant, pour l'exposition réalisée par PSL en 2014, une équipe franco-allemande a entrepris le travail engagé voici deux siècles. Elle propose une première traduction visuelle des instructions de Wilhelm : la carte générale des langues parlées en Europe.

Otherness as an intellectual horizon

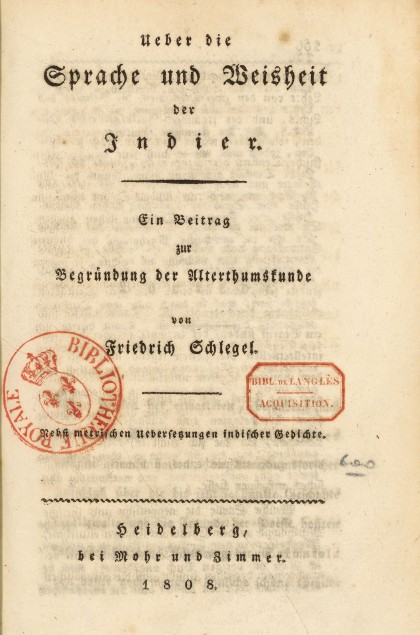

Friedrich Schlegel, 1808, Bibliothèque nationale de France, © Bibliothèque nationale de France

India, the cradle of Europe

The study of ancient non-European civilizations deeply influenced Europe's perception of its own history and identity. In France, Napoleon's Egyptian Campaign inspired wild public enthusiasm (Egyptomania) for the Reign of the Pharaohs, while in Germany, Friedrich von Schlegel and Franz Bopp's pioneering work in linguistics, positing that numerous European languages originated in India, caught the public eye.

Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier (Research on the Language and Philosophy of India), published in 1808, is one of the most significant works of the period. Schlegel, using his observations of Sanskrit and Amerindian languages, postulated that the study of linguistics must be based on comparative grammar rather than on lexicographic comparisons. This new approach to the discipline led to the development of comparative grammar and modern-day comparative linguistics.

The Humboldt brothers, as long-time students of non-European civilizations, inspired and encouraged their fellow scholars to pursue innovations in linguistics and supported numerous research projects in the field.

Egyptian hieroglyphs

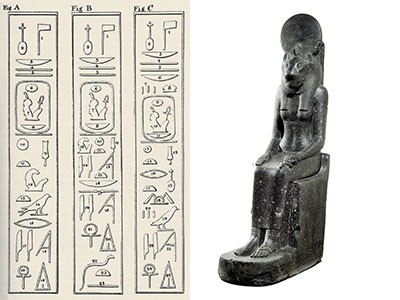

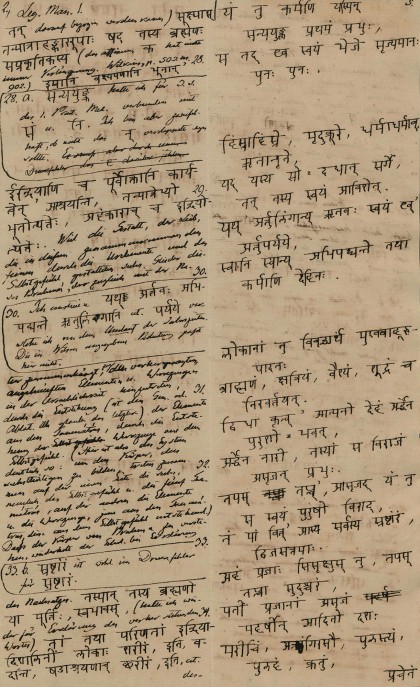

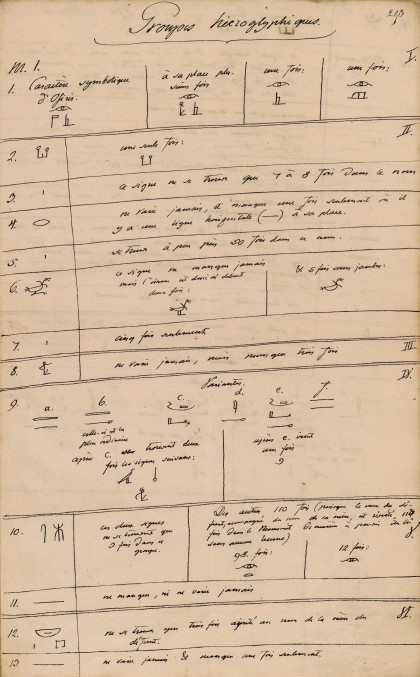

Jean-François Champollion's decipherment of the Rosetta stone hieroglyphs was a pivotal moment in our understanding of Ancient Egypt. Wilhelm von Humboldt met Champollion through his brother Alexander, and the two began a correspondence that lasted from June 1824 to July 1827. From Champollion, Wilhelm learned that the Egyptian hieroglyphic system contained both ideograms (figurative representations) and phonograms (phonetic representations) similar to European alphabets.

Humboldt used Champollion's deciphering system to translate inscriptions found on the statues of the Goddess Sekhmet; and on March 24th, 1825, presented a communication on Egyptology, Über vier Äegyptische löwenköpfige Bildsäulen in den hiesigen Königlichen Atnikensammlungen (On four Egyptian sculptures with lion's heads from the royal collection of antiquities of Berlin) to the Berlin Academy of Sciences. Thanks to their correspondence, Wilhelm was able to convince the heretofore-skeptical German scientific community to accept Champollion's deciphering system. Champollion, in turn, provided Wilhelm with the information required to support and develop his theory of linguistics.

Wilhelm von Humboldt, Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Handschriftenabteilung, Coll. ling. fol. 152. p. 5 recto. © Berlin, Staatsbibliothek

Wilhelm von Humboldt, 1824, Encre sur papier, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département des Manuscrits, NAF 203573, fol. 253, © Bibliothèque nationale de France

fragment 1. 16th century, 405,5 x 22,5 cm, Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Hanschriftenabteilung, MS. amer. 2, © Berlin, Staatsbibliothek

Amerindian hieroglyphs

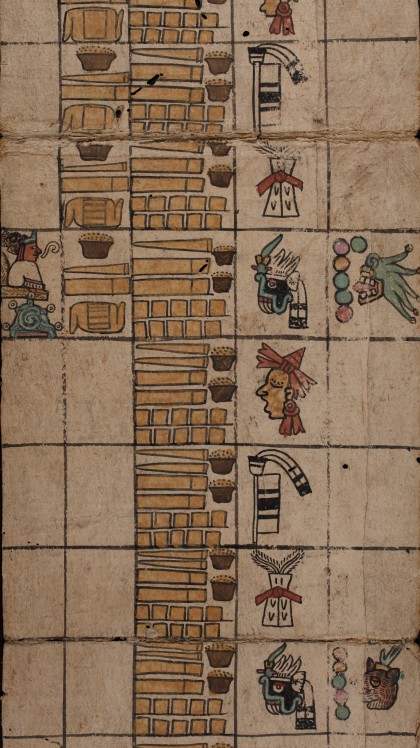

Alexander von Humboldt was also interested in hieroglyphs, but devoted his efforts to studying those found in the Americas. In his Views of the Cordilleras and Monuments of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, he presents the Mexican codices he brought back from his travels and others he uncovered in the libraries of Paris, London, Rome and Dresden.

To Alexander, the significance of these "monuments" goes far beyond their aesthetic value; he believes that they play an integral part in his description of Man and Nature because they each translate a specific worldview and a unique perspective on observed Nature. Alexander focused on analyzing Aztec maps, calendars and numeral systems in order to better understand the relations between the region's various ancient population groups and also to uncover possible universal principals linking the different systems.

A quest for languages

Language and worldview

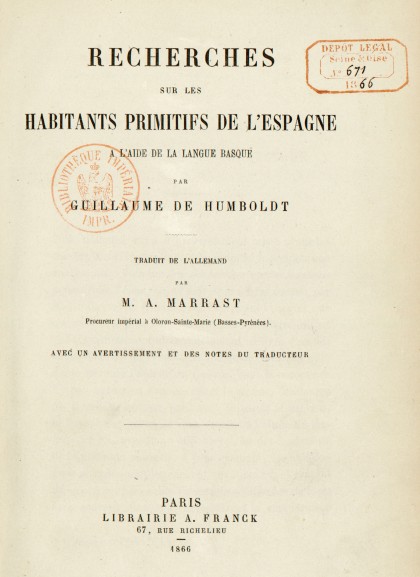

On December 31st 1819, Wilhelm resigned his last official position and retired to his Tegel estate. From thereon, he devoted himself to intellectual pursuits, with a particular focus on his research on language and languages. Wilhelm built one of the most extensive collections of non-European linguistic materials in Europe: lexical lists, texts, grammars … thanks to his own field work in Spain, France Rome, England and Germany and to the data collected in the Americas by his brother Alexander. His research also benefited from the productive exchanges he developed and maintained with other specialists such as the French sinologist Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat, John Crawfurd in England or John Pickering in the United States.

According to Humboldt's theory, "Language is the formative organ of thought." Moreover, he believed that language is not only a means of communication but also a precondition for the possibility of cognition. It follows that each language, as a product of thought, engenders a specific "worldview". For Humboldt, each language has its own specific linguistic structure, its own identity and that structure itself produces an equally specific worldview.

Wilhelm also argued for the necessity of developing comparative linguistics. In June 1820, Wilhelm von Humboldt addressed the Berlin Academy for the first time. Amongst other topics, he outlined a plan for the creation of a gigantic analytic system to compare all world languages; a project he had already formulated in Paris twenty years earlier.

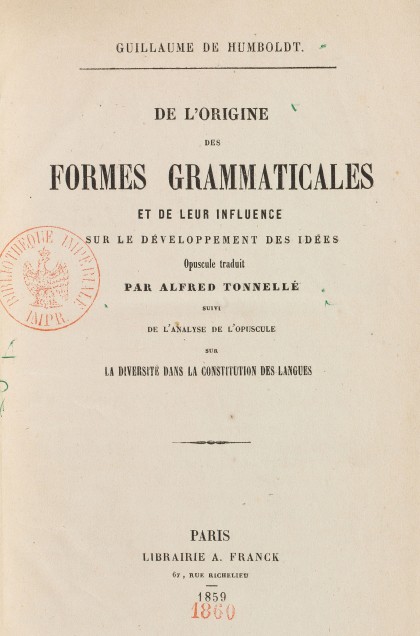

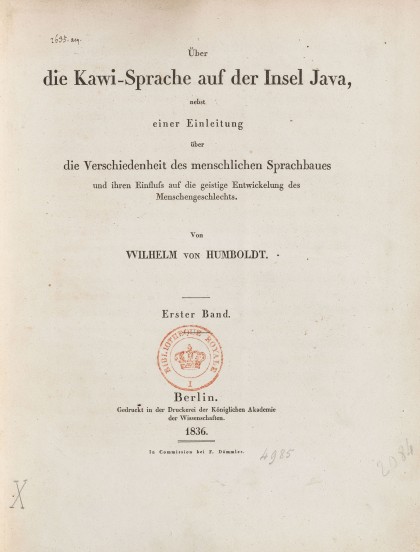

Wilhelm von Humboldt, 1836, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Littérature et art, X-4985, © Bibliothèque nationale de France

The Kawi language of Indonesia

Wilhelm von Humboldt passed away at Tegel Castle in 1835, leaving the book summarizing his groundbreaking linguistics project unpublished. His last and most remarkable work was a comprehensive study in three volumes: Über die Kawi sprache aufder Insel Java (On the Kawi language of the isle of Java). One year after his death, his brother Alexander published the work posthumously. It embodies a lifetime of research, thought and theory on linguistics and anthropology. In his introduction, Wilhelm outlines his general observations on the language and explains the empirical methodology he used to study both the grammatical structure and the literature of Kawi and other Austronesian languages.

Wilhelm von Humboldt is undoubtedly the most important Philosopher of Language of his time and one of the founding fathers of modern linguistics. Unfortunately, his theories were not always well received in the 19th century.

20th century linguistics scholars however, have rediscovered and reconsidered his work, either via the cultural theory of linguistics (Vossler) or structural linguistics (Saussure, Benveniste, Bloomfield, Whorf, Chomsky). He has been an inspiration to all philosophers of language with the exception of those that hail from the Anglo-Saxon school of analytic philosophy.

Comparative anthropology

Early 19th century intellectuals focused considerable energy on questions regarding the origins of Man and the diversity of Mankind. The Humboldt brothers were no exception; they however, took what we would now call a cross disciplinary approach to the subject, mixing anthropology, philosophy and politics. By studying the cultures, civilizations and languages of ancient and modern peoples, the Humboldt brothers were able to use the past to analyze and understand the present.

Classical Antiquity

The art and culture of ancient Greece and Rome remained a major source of inspiration in early 19th century Europe. Wilhelm von Humboldt was particularly influenced by the example of ancient Greece. While posted to Rome (1803-1808), Wilhelm planned to write a study of Demosthenes and other Ancient Greek orators.

In reality, he was far less interested in the literary and linguistic qualities of Demosthenes' discourses than he was fascinated by classical cultural and political history.

In a letter to Jean Geoffroy Schweighaeuser dated November 4th 1807, Wilhelm announced his intention to write a history of the decline and fall of the Greek Republics:

His goal was to uncover the essence of ancient Greek thought (that he did not hesitate to compare to contemporary German thought) and understand the character of the ancient Greek nation. Encouraged by his work on ancient Greece and later on ancient Rome, Wilhelm went on to study other nations.

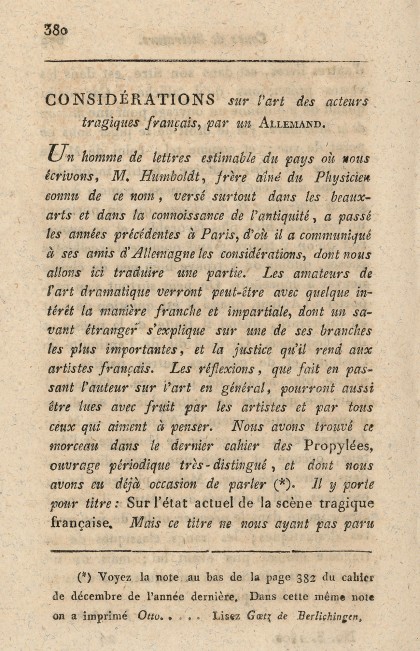

The French character

Wilhelm began developing the concept of comparative anthropology around 1800, while living in Paris. His initial research was devoted to European cultures; he studied the French, the Germans and the Basques. Wilhelm's Paris notebooks illustrate his meticulous observation of the "national character of the French".

Although his research on comparative physiognomy was a failure, his research in the areas of culture and aesthetics was more productive. For example, he published an important study on French theater. The concept of character - of an individual, a language, a nation, an era – became a leitmotiv in Wilhelm von Humboldt's thought and work.

Related events and resources

Exhibition at the CROUS de Paris

In 2014, Paris Sciences et Lettres produced its first exhibition, in close collaboration with researchers and prestigious institutions in France and in Germany. One year later, PSL and the CROUS de Paris joined forces to bring the exhibit to the heart of our academic community. At the Centre Sarrailh, students, faculty and staff could visit and revisit the exhibit, discover and draw inspiration from Alexander and Wilhelm von Humboldt and their extraordinary lives of travel, scientific discovery, innovation and accomplishment.

Dates: September 1st through December 18th 2015 Entry: Free of charge

Opening hours: Open to the public Monday tnrough Friday from 9:30 am to 4::30 pm.

Place: Centre Sarraih, 39 avenue Georges Bernanos, 75005 Paris

Catalogue of the exhibition

Les frères Humboldt. L'Europe de l'esprit, publisher: De Monza, 2014, 200 pages.

This catalogue accompanies the exhibition "Les frères Humboldt, L'Europe de l'Esprit" (The Humboldt brothers – The Spirit of Europe) produced by Paris Sciences & Lettres (PSL) and shown at the Observatoire de Paris from May 15th through June 30th 2014. The catalogue is divided into 5 sections, mirroring the exhibition's main themes: "Matrix: family background and contemporary interest in classical Antiquity", "Res Publica: Revolution. Regeneration", "Europe and the World: Otherness as an intellectual horizon", "Morphologies: of parts and the whole", and "Sharing knowledge". The catalogue is far more than a simple visual reminder of the exhibition (maps, objects, letters and publications), it is also a theoretical work comprising 10 essays written by eminent scholars.

Throughout the catalogue, insets by Laurence Bobis, Director of the Observatoire de Paris library, provide the reader with additional bibliographic, political and scientific information. The catalogue is designed for the general public, for visitors to the exhibition and for informed or academic readers. Its intention is to prolong the exhibition experience and emphasize the intellectual, philosophical and ethical values to which the Humboldt brothers devoted their lives. These brilliant polymath intellectuals, one focused on science, the other on the humanities, were driven by a deep and unwavering humanism and a shared vision for a unified Europe, founded on progress and knowledge.

The catalogue can be found on most on-line book platforms as well as at the l'Ecume des pages bookshop (174 Boulevard Saint-Germain, 75006 Paris).

About the exhibition

This virtual exhibition follows on the physical exhibition The Humboldt brothers – The Spirit of Europe held at the Observatoire de Paris from May 15th through July 11th 2014. A smaller physical version of the exhibition was shown in 2015 at the Centre Sarrailh, 39 avenue Georges Bernanos, thanks to a PSL /CROUS de Paris partnership.

The Humboldt brothers have become a symbol of the intellectual, philosophical and ethical values that bind France and the Germanic World despite their tumultuous political history: a fascination for classical Antiquity and a deep attachment to rationalism and universalism. The exhibition is a first for PSL - Paris Sciences et Lettres Research University, and the first French exhibition devoted solely to the Humboldt brothers. Our goal: to open a window onto the extraordinary intellectual effervescence of a era when anything was possible, by presentation the life and work of two stellar intellectuals, their insatiable curiosity for the world around them, their commitment to advancing and sharing knowledge and science, and their incredible talent for innovation.

The Humboldt brothers influenced generations of intellectuals and scholars the world over. PSL shares their fundamental belief in the unity of the Sciences and the Arts and the academic ideals they defended: a university founded on the principles of scientific excellence, where academics and research are intimately linked, and where all disciplines coexist without boundaries, from astrophysics to the visual and performing arts, from mathematics to the humanities.

Click here to download the press kit [1502.0Ko]

Physical exhibition curated by

Bénédicte Savoy, Professor of Art history, Berlin

David Blankenstein, graduate in art history and museum studies

Produced by

Paris Sciences et Lettres Research University (PSL), in partnership with Labex TransferS.

Scientific Committee

Under the chairmanship of Marc Fumaroli, member of the Académie française.

- Elisabeth Beyer - cultural attaché in charge of books at the French Embassy in Germany

- Laurence Bobis - Director of the Observatoire de Paris library

- Monique Canto-Sperber - (then) President, Paris Sciences et Lettres Research University

- Barbara Cassin - Director of Research, CNRS

- Michel Espagne - Director, Labex TransferS

- Ottmar Ette, Professor - University of Potsdam

- Christine von Heinz – owner of Tegel Castle and the castle archives

- Ulrich von Heinz - owner of Tegel Castle and the castle archives

- Eberhard Knobloch – Professor Emeritus, Technische Universität Berlin (Technical University of Berlin)

- Michelle Lenoir, Director of the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle main library

- Central library - Henri Loyrette, Conseiller d'Etat, France

- Daniel Marchesseau, conservateur général honoraire du patrimoine (honorary Conservator General of Culture)

- Hermann Parzinger, President of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian cultural Foundation)

- Jürgen Trabant, Professor Emeritus, Die Freie Universität Berlin (Free University Of Berlin)

Acknowlegements

Marc Fumaroli and Monique Canto-Sperber would like to thank:

The Honorables Susanne Wasum-Rainer, German Ambassador to France

Mr. Louis Gallois and Mr. Louis Schweitzer, Commissaires généraux à l'investissement (Frenchgovernment investment comissioners)

Mr. Claude Catala, President, the Observatoire de Paris

The founding members of the Paris-Sciences et Lettres Foundation, members of Labex TransferS and and its Director Michel Espagne

La République des Savoirs and its director Antoine Compagnon

As well as:

Emmanuel Suard and Hubert Guicharrousse (Berlin, French Embassy in GermanyAllemagne), Hinrich Sieveking (Munich, Winterstein collection ), Heinrich Schulze Altcappenberg (Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett SMB-PK), Isabelle le Masne de Chermont (Paris, BNF), Caroline Noyes and Gabriel Carlier (Paris, MNHN), Manfred Gräfe and Cornelia Gentzen (Berlin, Stiftung Stadtmuseum, Humboldt-Sammlung Hein and Hausarchiv), Hans-Dieter Nägelke and Claudia Zachariae (Berlin, Technische Universität, Architekturmuseum), Stéphanie Baumewerd, Annick Trellu and Philippa Sissis (Berlin, Technische Universität, Art History Institute), Elisabeth Michel (Berlin), Sandrine Maufroy (Paris, Université Paris 4-Sorbonne), Emilie Oléron Evans (London, Queen Mary, University of London), Marie-Ange Maillet (Paris, Université Paris 8-Saint-Denis), Vincent Platini (Berlin, Freie Universität), Leah Stearns (Monticello, Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello).

Project coordinators

Hélène Chaudoreille

Véronique Prouvost

Virtual exhibition production

Nathalie Figueroa

Assisted by

Annael Le Poullennec and the team at the PSL Resource and Knowledge department

Dimitri Le Meur, ENS.

Translation

Robin Silver-Delouvrier (French to English)

Voice recordings (readings)

Thomas Claret, Alice Billon, Anne Buers

Image credits

- Gottlieb Schick, Wilhelm von Humboldt, 1808, oil on canvas, 86 x 66 cm, © Berlin, Deutsches Historisches Museum

- Henry William Pickersgill, Alexander von Humboldt, 1831, oil on canvas, 142,2 x 109,2 cm © Bridgeman Art Library

- Johan Weitsch, Humboldt et Bonpland au pied du Chimborazo en Equateur (Humboldt and Bonpland at the foot of mount Chimborozo...), 1806, oil on canvas, 163 x 226 cm © BPK, Berlin, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Hermann Buresch

- Wilhelm von Humboldt, Anleitung zur Entwerfung einer allgemeinen Sprachkarte [Instructions for making a general map of spoken languages], annex to a letter from Wilhelm von Humboldt to Goethe dated November 15th 1812, ink on paper, © Weimar, Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Goethe und Schiller-Archiv