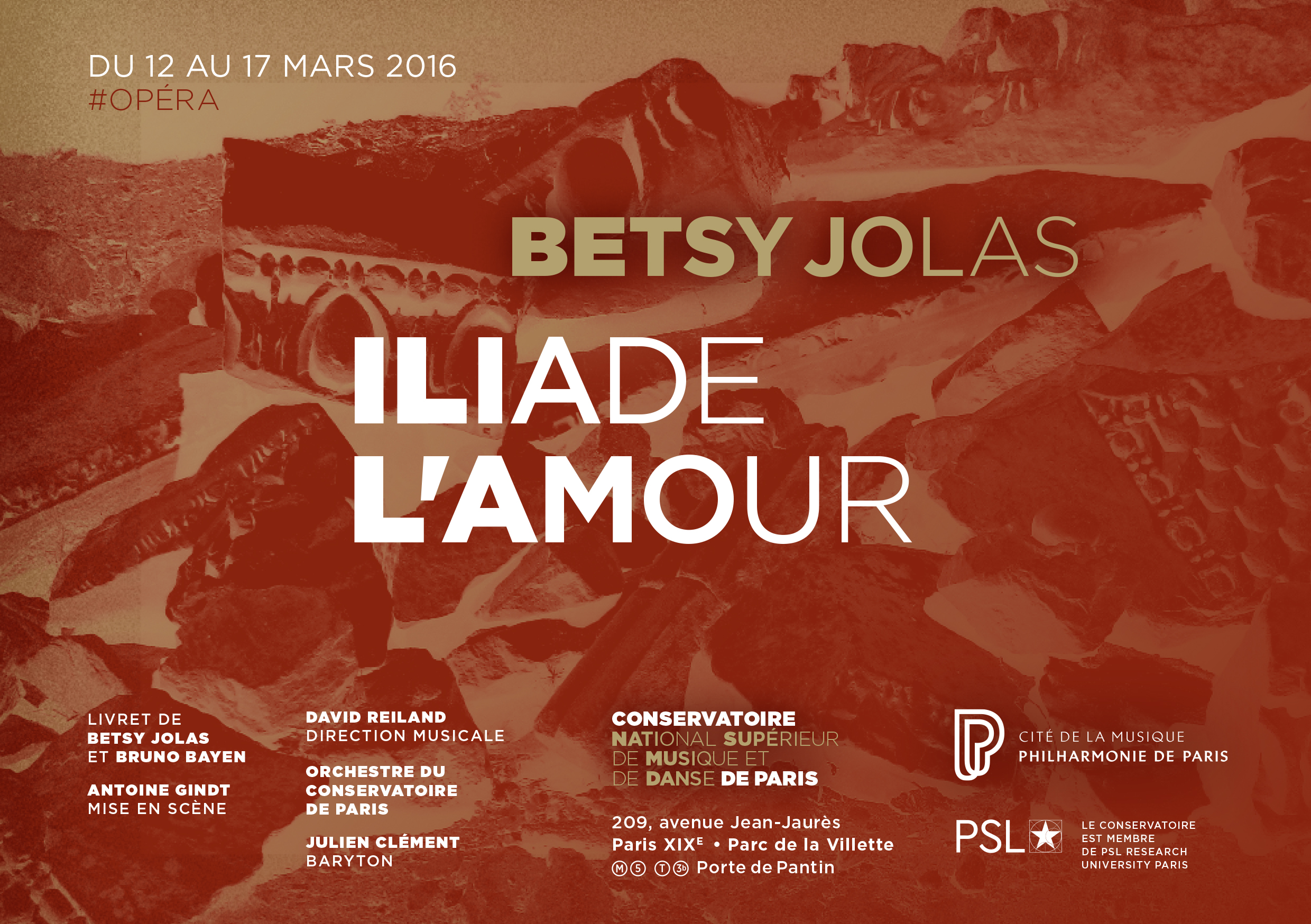

Iliade l’amour, a Conservatoire Opera

The Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse and the Philarmonie de Paris present Iliade l’Amour, an opera by Betsy Jolas. This new work is the result of a collaboration between professors and students in the vocal, instrumental, and choreography departments of the Conservatoire; the scenography, meanwhile, was created by one teacher and four students from the EnsAD.

Genesis

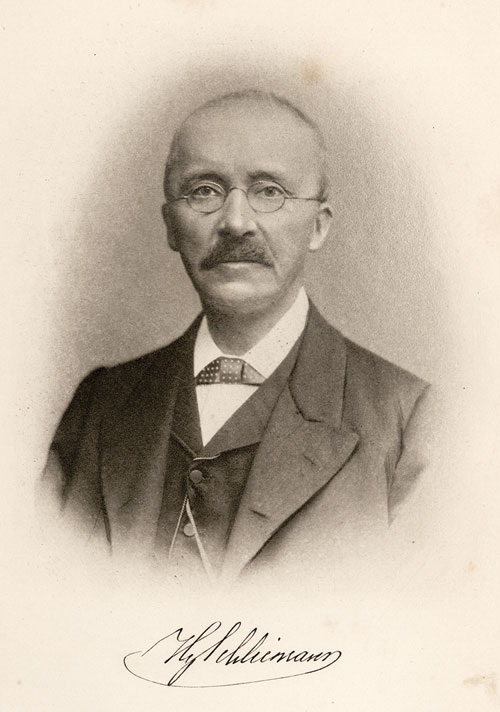

The opera is a voyage through the autobiography of Heinrich Schliemann, a singular 19th century figure: at once a businessman and a pioneering archaeologist, he was fascinated by Home’s Iliad and made a controversial claim to have discovered the site of Troy. Stage director Antoine Gindt describes him in the following terms:

"Based on the story of Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890), who dedicated his vast fortune to his passion for archaeology and who unearthed the remains of Troy and later of Mycenae, Bruno Bayen created the play ‘Schliemann, unknown episodes’. The play was staged on the 26th May 1982 at the Chaillot Theatre, with Antoine Vitez cast as the lead. Composer Betsy Jolas adapted Bayen’s play into a long format opera in three acts, simply entitled ‘Schielmann’, which premiered on 3rd May 1995 at the Opéra de Lyon, stage directed by Alain Franco and directed by Kent Nagano (on a libretto by Bruno Bayen). Twenty Years later, Jolas has completed a new and extensively reworked version of her opera, with a reduced orchestra of 16 soloists and a length of one hour forty-five minutes. The libretto has also undergone extensive rewriting and has retained as its title that of the first part of Bruno Bayen’s text, Iliade l’amour. Jolas’ new version consists of ten tableaux.

Iliade l’amour offers a voyage through Schliemann’s life, narrated by his daughter, Andromache. The opera mixes the registers of historical realism and romanesque adventure with dreamlike elements. Boats and ships are omnipresent, and we chose one as the principal space for our work: the metaphor that links a ship’s bridge with the theatre stage is a powerful one, at once an illustration and a tool for the staging of the opera.

I have not aimed to explore the historical reality of this extraordinary story, but rather to make it resonate today through the subtle music of Betsy Jolas.

How, using no more than the simplest of theatrical devices, might we evoke the magic of rediscovery?: as Schliemann unearthed his ruins, this opera looks to unearth a means of representing the fantastic folly of his undertaking. How best to render what Besty Jolas calls the ‘dream’ of Schliemann, the dream of this incredible character, with his often fraught relationships and his propensity to obsessively rewrite his own history?"

Discovering Troy?

Heinrich Schliemann was born in 1822 in Neubukow in northern Germany. It was his father, a protestant pastor fascinated by Antiquity, who first introduced Schliemann to Greek mythology, reading his son the Iliad and the Odyssey. The image of Troy in flames captivated the young Schliemann and left him convinced that some trace of the city’s walls must remain. Forced to abandon his studies at the age of fourteen, he worked as a clerk in Germany, an accountant in Amsterdam, and a trader in Saint Petersburg, before making his fortune in the United States.

At the same time, Schliemann had studied Greek, travelled throughout Germany, Sweden, Italy, Egypt, and Greece, before discovering India, China, Tunis, San Francisco, Havana, and Mexico City. Upon his return to Paris, he began to study archaeology at the Sorbonne whilst maintaining his business.

In 1868, an edition of the Odyssey in his pocket, he travelled all throughout Ulysses’ homeland of Ithaca. By way of a politically advantageous encounter – with the vice counsel of the United States to the Dardanelles, Frank Calvert – Schliemann was able to begin digging on what he suspected was the former site of Troy. This was to be the first of seven successive archaeological expeditions, which critics would later denounce for their lack of scientific rigour. Yet despite flaws in his dating of the sites, Schliemann had indeed discovered the site of Homeric Troy.

He uncovered numerous objects, including what he believed to be Priam’s treasure and the jewels of Helen – which the Turkish government would accuse him of pillaging. Schliemann’s finds were gifted to the German nation and went on display, only to disappear during the Second World War until they reappeared at the Pushkin museum in Moscow in 1991; negotiations for the return of the treasure to its official owner, the Museum of Prehistory and Protohistory in Berlin, are still on-going.

A ‘chamber’ opera

Iliade l’amour inherits a great deal from 20th century opera. The treatment of the voice is reminiscent of Schonberg’s work Pierrot lunaire, a work constructed using scenes and archetypes borrowed from throughout the operatic genre. In Jolas’ work, duets (a love scene between Schliemann and Sophie (scene V), Sophia’s lullaby (scene VI) and a rapid enumeration by a gymnastics teacher (scene V) recall the catalogue aria of Motzart’s Don Giovanni.

Betsy Jolas describes her music, not as radically modern, but as personal; she looks for a "beautiful music that sounds right," searching for an equilibrium between consonance and dissonance. However, it is not a question of a return to tonality but rather tracing the kind of elegant melodic lines that bring to mind the musicians of the Middle Ages and of the Renaissance: Guillaume Dufay, Josquin Desprez, and Roland de Lassus, for example.

Betsy Jolas describes her music, not as radically modern, but as personal; she looks for a "beautiful music that sounds right," searching for an equilibrium between consonance and dissonance. However, it is not a question of a return to tonality but rather tracing the kind of elegant melodic lines that bring to mind the musicians of the Middle Ages and of the Renaissance: Guillaume Dufay, Josquin Desprez, and Roland de Lassus, for example.

Jolas is fascinated by the voice, and deploys it both to drive the action of the piece and as an instrument in its own right. Singing is often lyrical and elaborate in the more expressive moments of her work, wherein the narrative is suspended; dialogues, on the other hand, are characterized by a more recitative delivery. Melodrama (spoken text set to music) contrasts with more unusual forms in Jolas’ composition: in places the line between speaking and singing is blurred; elsewhere the voice is held for extended periods of time, punctuated with cries or laughter, or delivered with the mouth partially or entirely closed.

Working thus on the voice and its possibilities, the piece enriches at once the aural palette and the text itself, translating into music the tonic accents of language, its inflections, mute vowels or punctuation. The opera mixes French, English, German, and Greek, bringing about rhythmic changes as metrics vary to underline intonation. The trained ear will pick up on the composer’s taste for quintuple metre, a trait – appropriately enough given the subject matter – that is characteristic of ancient Greek hymns.

The choice of a baritone tessitura for Schliemann’s mature character contrasts with the high-pitched soprano of the youthful and fragile Sophia. In the lovers’ duets, Sophia’s melismata translate her unchained emotion that is thrown into relief by Schliemann’s obstinate resolve. Andromache projects a more even image with her mezzo-soprano tessitura, yet her numerous melismata betray a barely concealed anger.

As its subtitle – ‘a chamber opera’ – suggests, Iliade l’amour calls for an ensemble of sixteen musicians. Though scaled-down orchestra might appear fairly traditional at first glance, it in fact contains a number of surprises: violinists are absent, yet a synthesizer-sampler duo adds subtle ocean and radio sounds to the sonic background.