First discoveries (1898-1906)

Polonium and Radium

The main problem that Pierre and Marie Curie needed to overcome in their joint research project was that of procuring the raw material. They required large amounts of uranium-rich minerals. One of these minerals – pitchblende – was mined in Bohemia and used to colour glass.

Thanks to the generosity of Baron Henri Rothschild, the Curies agreed a partnership deal with the glassworks in Bohemia and we able to import several tonnes of the mineral from Sankt-Joachimsthal. This agreement enabled them to develop the chemical processes to separate, isolate and define the chemical properties of the unknown elements they were looking for.

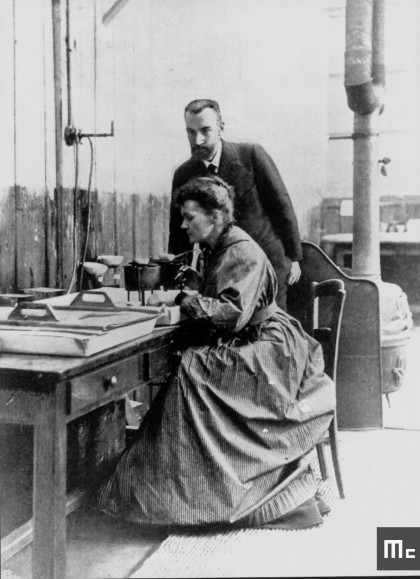

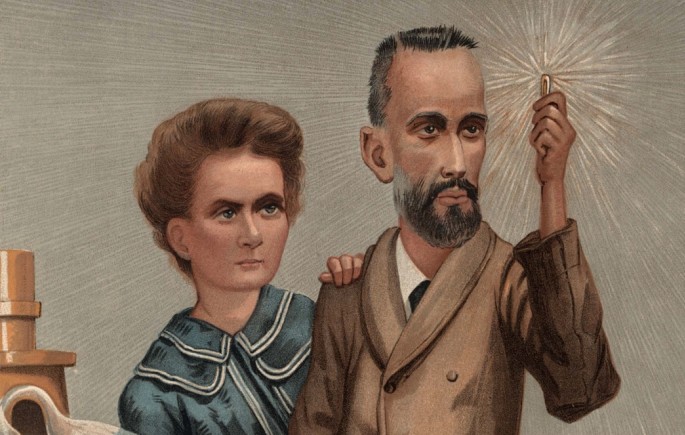

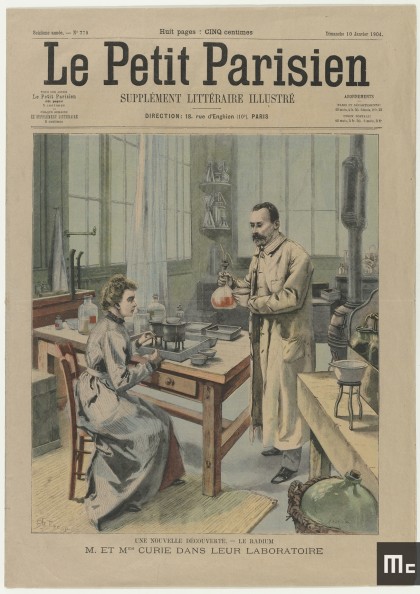

This was how the couple came to prove the existence of two previously unknown radioactive elements, present in very low quantities in uranium-rich minerals. On 18 July 1898, they announced their discovery of polonium (named in honour of Marie Curie’s homeland) and on 26 December of the same year, they announced their discovery assisted by Gustave Bémont, of the second new element, which they called radium.

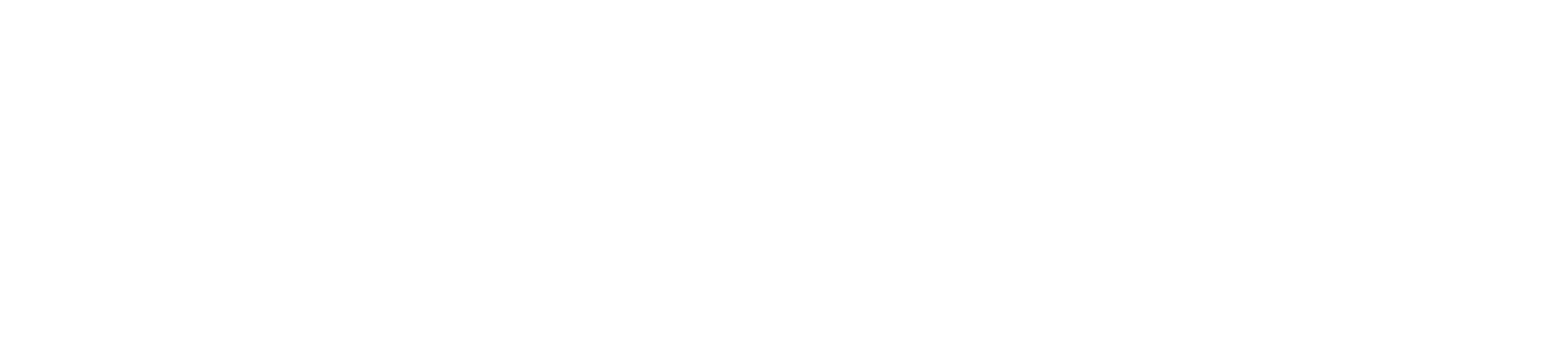

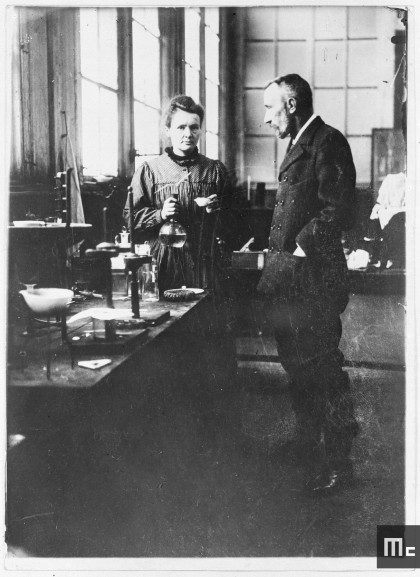

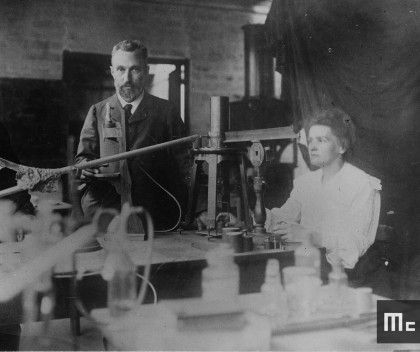

Following these discoveries, they continued their study of radioactivity. To facilitate their chemical work, Pierre and Marie were granted the use of a hangar in the courtyard of EMPCI.

Through their tireless work, the Curies were eventually able to produce one decigram of pure radium in 1902. This enabled them to measure the atomic weight of radium and thus identify the position of this element in the periodic table.

On 25 June 1903, Marie Curie defended her doctoral thesis entitle “Research on radioactive substances” for which she was awarded distinction.

The Nobel Prize in Physics (1903)

1903 was the year of consecration for Marie Curie. The couple travelled to London for the first time on 19 June to present their research to the Royal Institution. Pierre visited the city again a few months later to receive the Davy Medal, jointly awarded to himself and his wife by the Royal Society for their discoveries.

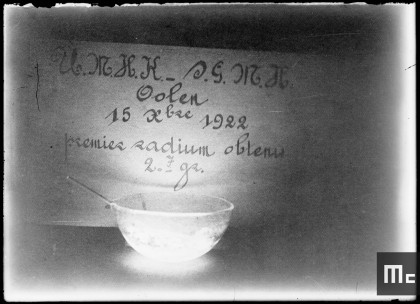

Already well-known in scientific circles, Pierre and Marie Curie became widely-known public figures on 12 December 1903, when it was announced that they were to be awarded, along with Henri Becquerel, the Nobel Prize in Physics “in recognition of the extraordinary services they have rendered by their joint researches on the radiation phenomena discovered by Professor Henri Becquerel.” Their scientific work had indeed contributed to establishing a new world-view of the atom and the properties of matter.

The prize was a reward for their research, but it also had an unsettling effect on the Curie’s lives. Despite the notoriety that came since winning the Nobel Prize, their working conditions were inadequate and the process to isolate radium remained long and difficult. As the Curie’s were so worn out by their work, they had to wait until 1905 before being able to travel to Stockholm to collect the award. They continued their research, although somewhat disturbed by journalists and other curious spectators.

New opportunities and another daughter

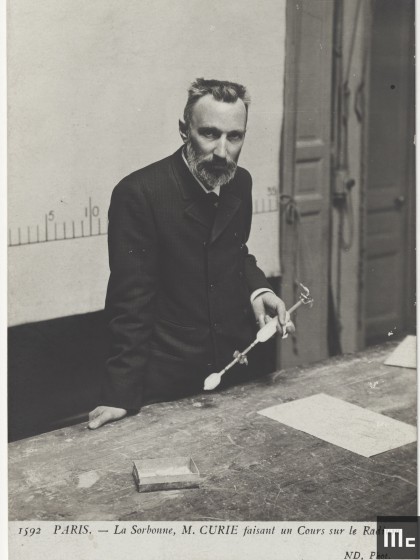

Winning the Nobel Prize did however bring about some advantages. From October 1904, Pierre became a Titular Professor of Physics at the Sorbonne Faculty of Sciences. The position came with a small laboratory located in an annex at the university at 12 rue Cuvier.

Marie became Chief of the laboratory in November 1904, even though the couple didn’t leave the hangar at EMPCI until 1905.

Pierre and Marie developed an experimental protocol to extract radium from pitchblende.

The Curie’s selflessness, along with the fact that they believed the discovery of radioactivity had to potential to benefit humanity, meant that they decided not to patent their discovery, preferring instead to make their research universally available.

As a result, from 1904 they entered into a partnership with Émile Armet de Lisle (1853-1928), a manufacturer from Nogent-sur-Marne, just east of Paris, in order to develop a method for the chemical processing of radium. The partnership also enabled them to delegate part of their work.

At the end of the year, the Curies celebrated the birth of their second daughter, Eve, on 6 December.

Catastrophe of 1906

In 1905, Pierre was elected to the French Academy of Sciences. Between the laboratory and their family life, the Curies did not have much time to devote to their life in the public eye.

Pierre Curie was nearing the end of his life. On 19 April 1906, he was run over and killed. While walking to a session at the Academy of Sciences, he was knocked over by a horse-drawn carriage on rue Dauphine near Pont Neuf in Paris. The back left wheel of the carriage crushed his head and he died instantly. He was just 47 years old.

Bibliography

Please find below a selection of books on Marie Curie's life and scientific career.

Madame Curie, A Biography by Eve Curie, Da Capo Press, 2001

“Marie Skłodowska Curie (1867-1934) was the first woman scientist to win worldwide acclaim and was, indeed, one of the great scientists of the twentieth century. Written by Curie’s daughter, the renowned international activist Eve Curie, this biography chronicles Curie’s legendary achievements in science, including her pioneering efforts in the study of radioactivity and her two Nobel Prizes in Physics and in Chemistry. It also spotlights her remarkable life, from her childhood in Poland, to her storybook Parisian marriage to fellow scientist Pierre Curie, to her tragic death from the very radium that brought her fame. Now updated with an eloquent, rousing introduction by beast-selling author Natalie Angier, this timeless biography celebrates an astonishing mind and an extraordinary woman’s life.”

Ève Curie

Pierre Curie, with autobiographical notes by Marie Curie, by Marie Curie, Dover Publications, Inc., 2012

Marie Curie, A Life, by Susan Quinn, Da Capo Press, 1995

“One hundred years ago, Marie Curie discovered radioactivity, for which she won the Nobel Prize in physics. In 1911 she won an unprecedented second Nobel Prize, this time in chemistry, for isolating new radioactive elements. Despite these achievements, or perhaps because of her fame, she has remained a saintly, unapproachable genius. From family documents and a private journal only recently made available, Susan Quinn at last tells the full human story. From the stubborn sixteen-year-old studying science at night while working as a governess, to her romance and scientific partnership with Pierre Curie – an extraordinary marriage of equals- we fell her defeats as well as her successes: her rejection by the French Academy, her unbearable grief at Pierre’s untimely and gruesome death, and her retreat into a love affair with a married fellow scientist, causing a scandal which almost cost her the second Nobel Prize. In Susan Quinn’s fully dimensional portrait, we come at last to know this complicated, passionate, brilliant woman.”

About

This virtual exhibition has been created as a natural prolongation of the travelling exhibition "Marie Curie 1867-1934". Arranged by the Musée Curie in 2011 for the International Year of Chemistry, the exhibition serves to commemorate the centenary year of Marie Curie’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Translated in several languages, the exhibition has travelled continuously throughout the world. For further details on how to book the exhibition, click here.

Credits

The exhibition has been arranged by the Musée Curie, with support from the Foreign and European Affairs Ministry, the Association Curie Joliot-Curie, the Institut français, the Institut Curie and the National Center for Scientific Research CNRS.

All images are provided by the Musée Curie’s archives.

Arrangement of the Virtual Exhibition

Xavier Reverdy-Théveniaud

With help from

Annael Le Poullennec and the team at the PSL Resource and Knowledge department