A new life in Paris (1891-1897)

The Polish student

Maria Sklodowska, then aged 24, arrived in Paris at the Gare du Nord at the end of October 1891. She initially moved into a property on rue d’Allemagne (now named avenue Jean Jaurès), with her sister and brother-in-law, Casimir Dluski, who was living in exile from Poland and had met Bronislawa during her studies.

She then moved to rue Flatters, in the Latin quarter, in March 1892, in order to be closer to the Sorbonne. She enrolled in the Faculty of Science on 3 November 1891, determined to follow an education in Science and become a secondary school teacher in Poland.

Along with Maria, female students made up only 2% of the university.

On her university enrolment form, Maria adapted her name to the more French‑sounding Marie. Studious and rather financially deprived, she worked tirelessly to bring herself up to standard.

Lacking in confidence about her scientific knowledge, she chose not to take her Licenciateship exams in the Summer of 1892, preferring to re-sit her first year.

This enabled her to graduate top of her class for the Licenciateship in Physics in July 1893. The following year, she graduated third in her class with a Licenciateship in Mathematical Sciences.

Meeting Pierre Curie

Marie Sklodowska’s mentor, Gabriel Lippmann (1945-1921), was a professor at the Sorbonne. It was in his laboratory that she conducted a study commissioned by the Society for the Encouragement of National Industry on the magnetic properties of certain steels, for which she had received a scholarship. However, it was not an area of study she knew particularly well. In order to assist her, Marie was introduced to one of France’s experts in magnetism, Pierre Curie.

As the laboratory chief at the Municipal School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry in Paris (formally known as EMPCI, now called ESPCI) since 1882, Pierre Curie was already an experienced physicist. He was known throughout the scientific community for his work on piezoelectricity, a discovery he made with his brother Jacques, as well as his work on magnetism and symmetry in physics. He was well respected for his talent in designing experiments and his quick wit.

The two got on well and began to work together. In March, Marie sat in the audience as Pierre obtained his doctorate in Physics.

However, Marie’s plan had always been to go back to her home country and become a teacher. When she did return to Poland in the summer of 1894, Pierre wrote to her to persuade her to come back to live and work alongside him.

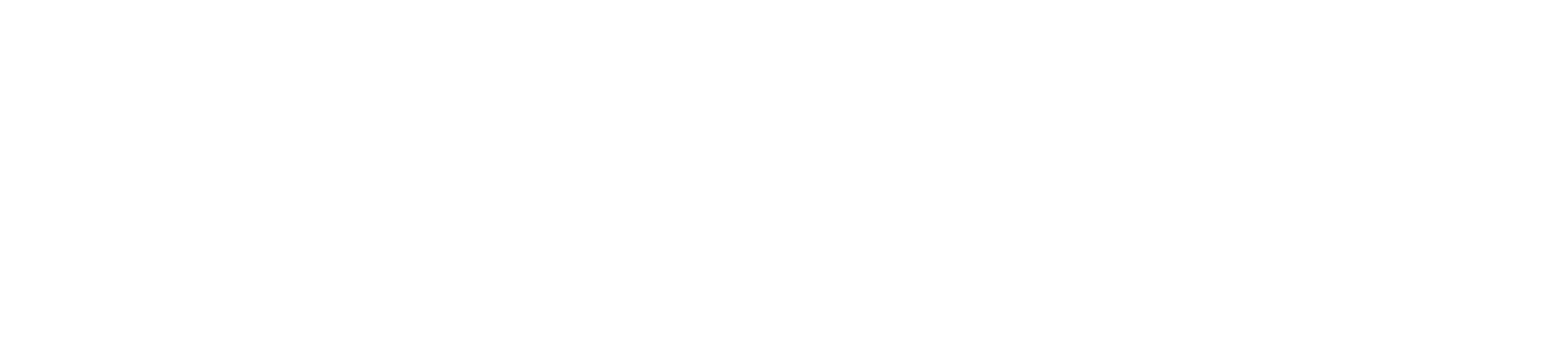

Marie let herself be convinced, and with her father’s blessing, she married Pierre Curie on 25 July 1895 in a small ceremony at the Town Hall in Sceaux, just south of Paris.

To celebrate their union, the couple bought themselves two state of the art bicycles – that had tyres! Their honeymoon was the first of many bike-riding holidays in Brittany. They then moved in to a property at 108 boulevard Kellermann in Paris.

Teaching, research and motherhood

Despite being married to a renowned physicist, the newly named Marie Curie still hoped to become a teacher. She took the “certificate of aptitude for teaching young women, mathematics” in 1896.

In October 1900, she was named lecturer of Physics for the 1st and 2nd year students at the higher education institute of École normale supérieure for young women in Sèvres, in the southwestern suburbs of Paris, where she continued to teach until 1906.

On 12 September 1897, Pierre and Marie’s first daughter, Irene, was born.

But that didn’t stop Marie from continuing her research. She published her first scientific paper on the magnetic properties of metal, for which she was awarded the Gegner Prize from the Academy of Sciences in 1898. She went on to win the same prize twice more in 1900 and 1902.

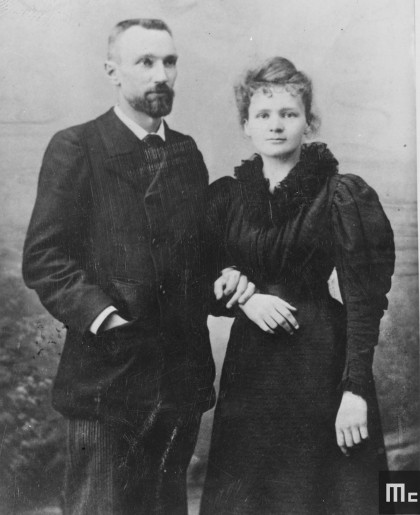

With the support of Pierre Curie, Marie decided at the end of 1897 to undertake a doctorate in physics on the invisible rays emitted by uranium, discovered 18 months earlier by Henri Becquerel (1852-1908). To work on these experiments, Marie made the most of the laboratory that the EMPCI had granted her and her husband.

She undertook a quantitative study of “uranium rays” with some highly sensitive equipment developed by Pierre Curie. She coined to term “radioactivity” to describe the spontaneous release of radium, established the atomic properties of this phenomenon and sought to identify whether or not radiation was also present, initially in other elements, then in uranium-rich minerals such as pitchblende. She set out the hypothesis that they contained an unknown element. Gabriel Lippmann presented this work to the Academy of Sciences on 12 April 1898. Pierre Curie, intrigued by the results, abandoned his own research to work alongside his wife.

Bibliography

Please find below a selection of books on Marie Curie's life and scientific career.

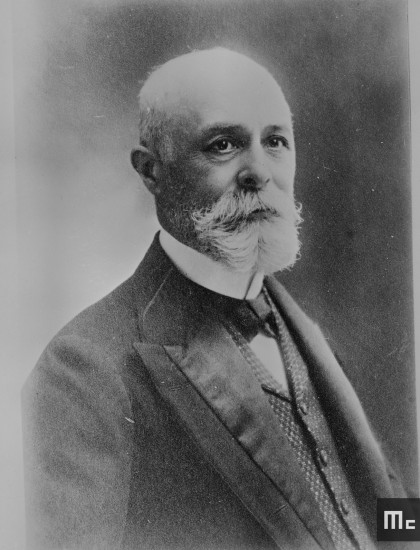

Madame Curie, A Biography by Eve Curie, Da Capo Press, 2001

“Marie Skłodowska Curie (1867-1934) was the first woman scientist to win worldwide acclaim and was, indeed, one of the great scientists of the twentieth century. Written by Curie’s daughter, the renowned international activist Eve Curie, this biography chronicles Curie’s legendary achievements in science, including her pioneering efforts in the study of radioactivity and her two Nobel Prizes in Physics and in Chemistry. It also spotlights her remarkable life, from her childhood in Poland, to her storybook Parisian marriage to fellow scientist Pierre Curie, to her tragic death from the very radium that brought her fame. Now updated with an eloquent, rousing introduction by beast-selling author Natalie Angier, this timeless biography celebrates an astonishing mind and an extraordinary woman’s life.”

Ève Curie

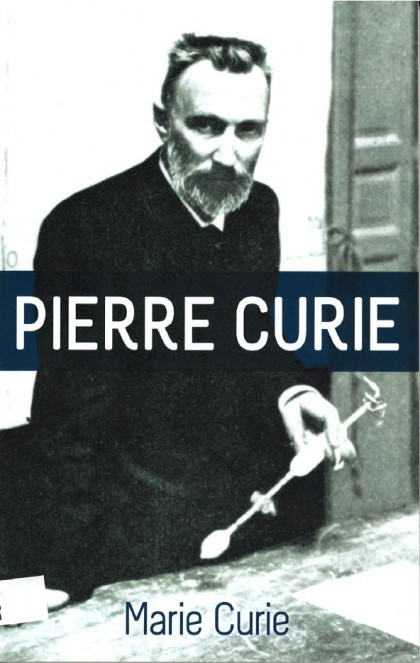

Pierre Curie, with autobiographical notes by Marie Curie, by Marie Curie, Dover Publications, Inc., 2012

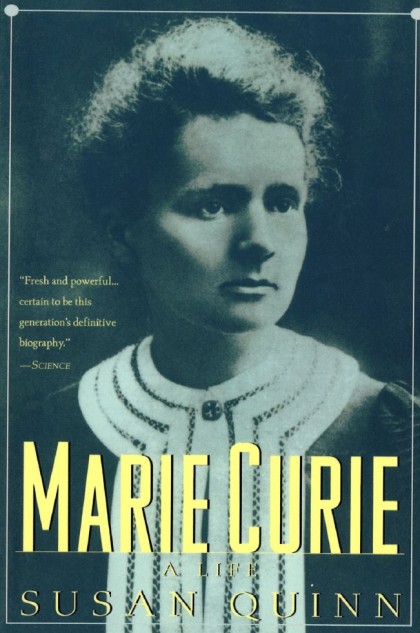

Marie Curie, A Life, by Susan Quinn, Da Capo Press, 1995

“One hundred years ago, Marie Curie discovered radioactivity, for which she won the Nobel Prize in physics. In 1911 she won an unprecedented second Nobel Prize, this time in chemistry, for isolating new radioactive elements. Despite these achievements, or perhaps because of her fame, she has remained a saintly, unapproachable genius. From family documents and a private journal only recently made available, Susan Quinn at last tells the full human story. From the stubborn sixteen-year-old studying science at night while working as a governess, to her romance and scientific partnership with Pierre Curie – an extraordinary marriage of equals- we fell her defeats as well as her successes: her rejection by the French Academy, her unbearable grief at Pierre’s untimely and gruesome death, and her retreat into a love affair with a married fellow scientist, causing a scandal which almost cost her the second Nobel Prize. In Susan Quinn’s fully dimensional portrait, we come at last to know this complicated, passionate, brilliant woman.”

About

This virtual exhibition has been created as a natural prolongation of the travelling exhibition "Marie Curie 1867-1934". Arranged by the Musée Curie in 2011 for the International Year of Chemistry, the exhibition serves to commemorate the centenary year of Marie Curie’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Translated in several languages, the exhibition has travelled continuously throughout the world. For further details on how to book the exhibition, click here.

Credits

The exhibition has been arranged by the Musée Curie, with support from the Foreign and European Affairs Ministry, the Association Curie Joliot-Curie, the Institut français, the Institut Curie and the National Center for Scientific Research CNRS.

All images are provided by the Musée Curie’s archives.

Arrangement of the Virtual Exhibition

Xavier Reverdy-Théveniaud

With help from

Annael Le Poullennec and the team at the PSL Resource and Knowledge department