An internationally known public figure (1919-1934)

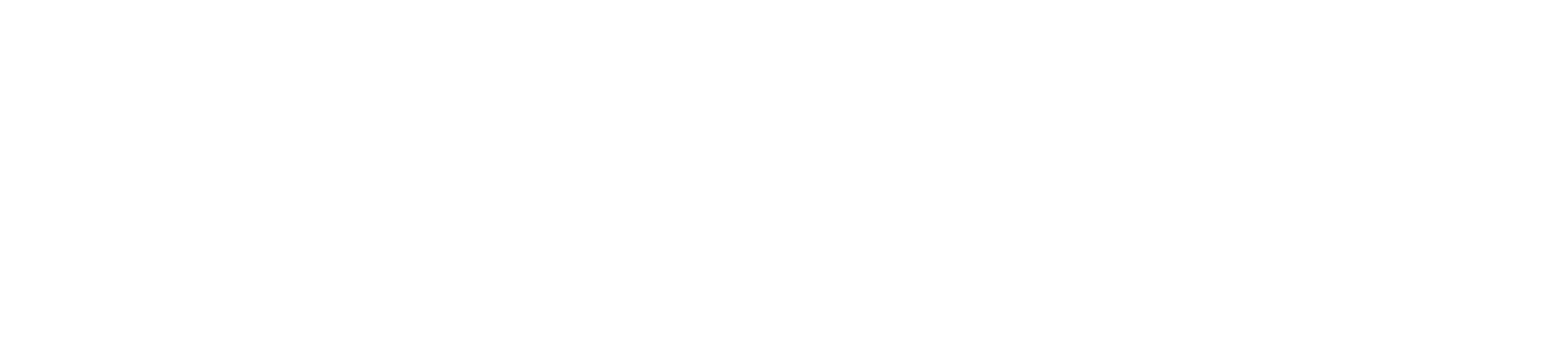

The Radium Institute, a modern laboratory

In 1909, the Pasteur Institute and the University of Paris signed a partnership to build a modern research laboratory for Marie Curie. It was to become the Radium Institute, financed by the legacy the important 19th‑Century philanthropist Daniel Iffla, known as Osiris (1825-1907).

The Institute opened in 1914 at 11 rue Pierre Curie (which has since been renamed rue Pierre et Marie Curie). Marie was Director of the Physics and Chemistry laboratory in the Curie Pavilion until her death in 1934.

The laboratory became a leading centre for research in radioactive bodies and helped develop the use of radiation in the fight against cancer. It was one of the main radioactivity research hubs in the world.

Marie Curie and Dr Claudius Regaud, the director of the Pasteur Pavilion at the Radium Institute, established in 1920 the Curie Foundation, which rapidly became seen throughout the world as a reference in radiation therapy to treat cancer. In 1921, the foundation was recognised as a public interest institution, encouraging donations that were used to fund the extension of the laboratories at the Radium Institute. The Curie Foundation sought also to set up two clinics with a view to developing therapeutic uses of radiation in cancer treatment.

Fifty years later, in 1970, the Curie Foundation merged with the Radium Institute. In 1978, it became known as the Institut Curie.

Once the war was over, Irene Curie became her mother’s personal laboratory assistant. Frederic Joliot took over her position in 1924, while Irene was preparing her thesis, just two years before the pair were to be married.

[To find out more about the Curie Laboratory, take a look at our online collection of logbooks and progress reports.]

Trip to United States

Marie Curie continued to teach, both at the Sorbonne and the Radium Institute, as well as at other establishments, including the Arts et Métiers university in Paris.

As the director of the laboratory, Curie was in great demand to participate in society life, a role that she did not particularly enjoy. Nevertheless, the need for research funding was becoming ever more pressing, given that the radium necessary for her work was both rare and expensive.

In 1921, the American journalist Mary Meloney (1878-1843), an admirer of Curie’s work, organised a fundraiser in the United States, putting together a committee of wealthy American women. The purpose was to offer Marie Curie a gram of radium, worth at that time around $100 000 dollars (equivalent to approximately $1,355,000 in today’s money).

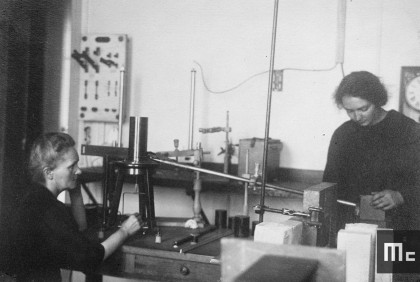

Accompanied by her daughters, Marie travelled to the United States, where she received a special welcome during her time there throughout May and June of 1921. Over the six week trip, she travelled along the east coast of the United States.

The President himself, Warren G. Harding, presented her with a golden key during an official ceremony at the White House on 20 May. The key opened a casket containing one gram of radium.

Curie gave talks at numerous conferences in women’s universities and colleges, who rewarded her with honorary diplomas. She also met with important industrials, including visiting the radium factory in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where the gram of radium she was given had been prepared. Even through the trip was extremely tiring, Curie developed fruitful relationships with many of her scientific and engineering peers.

She returned to the United States in 1929 to collect a second gram of radium, which she offered to the Polish Institute of Radium in Warsaw.

A world-renowned scientist

Having been accepted as a major figure in scientific circles, Marie Curie was invited to participate in numerous scientific and medical conferences around the world.

Her discoveries, her Nobel Prizes, and her commitment to research and fighting cancer earned her the recognition of her peers.

Under her leadership, research in radiation and its potential biological and medical uses was developed at the Radium Institute

In 1922, Marie Curie was elected to the Academy of Medicine.

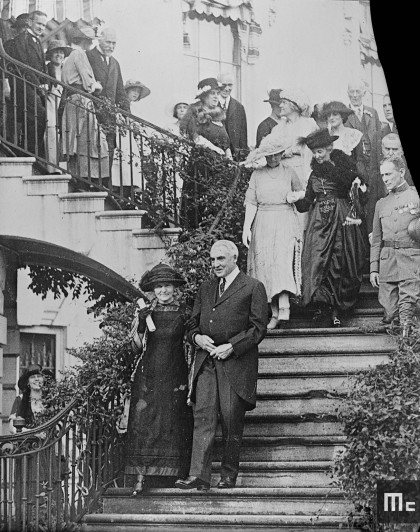

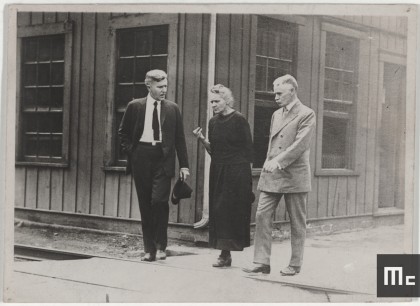

Marie Curie gradually gained greater international recognition. She visited many countries to promote the scientific work conducted in her laboratory, and research more generally.

She became the Vice President of the Commission for Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations in Geneva. There, she worked alongside Albert Einstein (1879‑1955), who she met at the first Physics Solvay Council, and the philosopher Henri Bergson (1859-1941). The Commission aimed to strengthen and consolidate initiatives supporting culture, science and peace.

Until her death in the summer of 1934, Marie Curie travelled the world meeting her scientific peers and accepting the many prizes and honours bestowed upon her. In particular, Curie’s travels took her to Prague in June 1925, Rio de Janeiro in July/August 1926 and Madrid in 1933.

Such recognition, although it came late in her life, rewarded a lifetime dedicated to her work and to science as a whole.

Video of the only sound recording of Marie Curie’s voice

In 1931, in Paris, Marie Curie received a Gold Medal from the American College of Radiology (ACR). The ACR donated the film to the Musée Curie that can be seen here in digital format.

Source: Musée Curie; with the authorisation of the ACR

Posterity

Irene and Frederic Joliot-Curie produced for the first time, at the Radium Institute, artificial radioactive isotopes in January 1934. Marie had the satisfaction of seeing her daughter and son-in-law making a major discovery in her laboratory.

However, unfortunately she did not get to witness the Joliot-Curie’s being awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in December 1935; she died of leukaemia on 4 July 1934 in Sancellemoz in the Haute-Savoie region in the French Alps. Her illness was clearly caused by her work on radioactivity and the use of x-rays during the First World War.

Marie Curie was a pioneer. Through her never-ending research work, she opened up an entirely new branch of physics. As the first woman to receive the recognition of the scientific community, she was a source of inspiration for many scientists, women in particular, throughout the world.

Recognition from the wider public has grown over time, reaching its height on 20 April 1995, when her ashes, along with those belonging to her husband Pierre, were transferred to the Pantheon in Paris. France sought to pay tribute to the young Polish immigrant who went on to become one of the most important scientists of the 20th Century.

Bibliography

Please find below a selection of books on Marie Curie's life and scientific career.

Madame Curie, A Biography by Eve Curie, Da Capo Press, 2001

“Marie Skłodowska Curie (1867-1934) was the first woman scientist to win worldwide acclaim and was, indeed, one of the great scientists of the twentieth century. Written by Curie’s daughter, the renowned international activist Eve Curie, this biography chronicles Curie’s legendary achievements in science, including her pioneering efforts in the study of radioactivity and her two Nobel Prizes in Physics and in Chemistry. It also spotlights her remarkable life, from her childhood in Poland, to her storybook Parisian marriage to fellow scientist Pierre Curie, to her tragic death from the very radium that brought her fame. Now updated with an eloquent, rousing introduction by beast-selling author Natalie Angier, this timeless biography celebrates an astonishing mind and an extraordinary woman’s life.”

Ève Curie

Pierre Curie, with autobiographical notes by Marie Curie, by Marie Curie, Dover Publications, Inc., 2012

Marie Curie, A Life, by Susan Quinn, Da Capo Press, 1995

“One hundred years ago, Marie Curie discovered radioactivity, for which she won the Nobel Prize in physics. In 1911 she won an unprecedented second Nobel Prize, this time in chemistry, for isolating new radioactive elements. Despite these achievements, or perhaps because of her fame, she has remained a saintly, unapproachable genius. From family documents and a private journal only recently made available, Susan Quinn at last tells the full human story. From the stubborn sixteen-year-old studying science at night while working as a governess, to her romance and scientific partnership with Pierre Curie – an extraordinary marriage of equals- we fell her defeats as well as her successes: her rejection by the French Academy, her unbearable grief at Pierre’s untimely and gruesome death, and her retreat into a love affair with a married fellow scientist, causing a scandal which almost cost her the second Nobel Prize. In Susan Quinn’s fully dimensional portrait, we come at last to know this complicated, passionate, brilliant woman.”

About

This virtual exhibition has been created as a natural prolongation of the travelling exhibition "Marie Curie 1867-1934". Arranged by the Musée Curie in 2011 for the International Year of Chemistry, the exhibition serves to commemorate the centenary year of Marie Curie’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Translated in several languages, the exhibition has travelled continuously throughout the world. For further details on how to book the exhibition, click here.

Credits

The exhibition has been arranged by the Musée Curie, with support from the Foreign and European Affairs Ministry, the Association Curie Joliot-Curie, the Institut français, the Institut Curie and the National Center for Scientific Research CNRS.

All images are provided by the Musée Curie’s archives.

Arrangement of the Virtual Exhibition

Xavier Reverdy-Théveniaud

With help from

Annael Le Poullennec and the team at the PSL Resource and Knowledge department